I am writing this blog post to accompany a manuscript of ours that has just been accepted in Functional Ecology. The link to the article is here. The final proofs are not yet ready, as of Sept 24, 2017, but the accepted manuscript is available, so I think it is safe to blog about it.

Darwin’s finches have been the focus of much intense study demonstrating how climatic fluctuations coupled with resource competition drive the evolution of a variety of bill sizes and shapes. Darwin’s finches are only found on the Galápagos Islands, located ~1000 km west of Ecuador in the middle of the Pacific ocean, pretty much along the equator. Climatically, these islands are typically considered warm to hot throughout the year, but also experience a relatively dry climate (<300 mm/year).

Darwin’s finches have been well studied with regard to the role of the bill in resource acquisition (i.e., searching for food, acquiring and crushing seeds etc.). Here is a young Geospiza searching for seeds in the relatively barren ground surface:

Bird bills are not dead structures, however. Bird bills are well vascularized (i.e. blood vessels are right below the beak keratin), while their limbs have specialized vasculature that promote heat loss or heat conservation, depending on the ambient conditions. In other words, these body surfaces (bill and legs especially) are “thermoregulatory windows“, which is a term used to refer to the fact that they can be “opened” and “closed” accordingly to dump or save body heat.

With this in mind, we hypothesized that Darwin’s finch bills have evolved in part for their role in thermoregulation, possibly co-opted, following adaptation for other functions. We predicted that bills of Darwin’s finches are effective thermoregulatory windows, and that species differences in morphology, along with physiology and behavior, lead to differences in thermoregulatory function.

To shed light on these hypotheses, we conducted a field study to assess heat exchange and microclimate use differences in three ground finch species and sympatric cactus finch (Geospiza). We collected thermal images of free-living birds during a hot and dry season and recorded microclimate data for each observation. We used individual thermographic data to model the contribution of bills, legs, and bodies to overall heat balance and compared surface temperatures to those from dead birds to test physiological control of heat loss from these surfaces. We derived and compared species-specific threshold environmental temperatures, which are indicative of a species’ thermally neutral temperature.

We could not formally test the question of adaptation in this study, but what this study represents is our initial observations of surface temperatures in four species of birds living within the same habitat. Conceptually, then, if they truly experience the same heat load and thermal regime (a null hypothesis), we would not observe differences in surface temperatures of bills, limbs, or feathers.

In all species, the bill surface was an effective heat dissipater during naturally occurring warm temperatures. We found that finches controlled surface temperatures through physiology (i.e. body surfaces exhibited different responses to changing heat loads) and that young birds had higher surface temperatures than adults. Larger bills contributed proportionally more to overall heat loss than smaller bills.

We demonstrate here that related, sympatric species with different bill sizes exhibit different patterns in the use of these thermoregulatory structures, supporting a role for thermoregulation in the evolution and ecology of Darwin’s finch morphology.

More work is to come, however. This study is still very much scratching the surface, and we hope to publish more on this topic in the months and years to come.

Below, I have attached some photos from our field work, and some summary data on the microhabitat patterns observed in the study:

My harshest critic. A small ground finch visited my desk one day to read my journal.

A flock of finches foraging on the ground

This mockingbird joined me every day to follow my work

Make-shift “hide” – mostly to shade my computer from overheating!

This mockingbird joined me every day to follow my work

Ray Danner and Russel Greenberg in action

A close-up of a small ground finch hanging out at our balcony.

A finch visiting our temporary habitat at the Charles Darwin Research Station – having a drink. Note how the bird’s legs are hot and swollen (this individual has avian pox)

A finch visiting our temporary habitat at the Charles Darwin Research Station

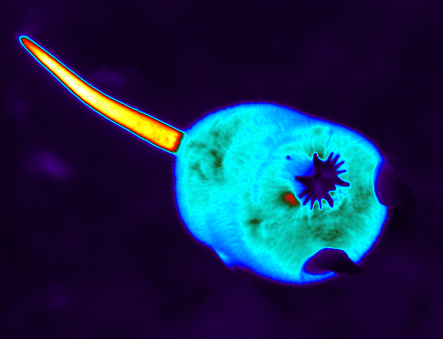

Sample thermal image from ~1 meter (finch hanging out in the shade)

Sample thermal image from ~1 meter (finch hanging out in the shade)

Small ground finch in the sun

Sample thermal image from ~2 meters

Sample thermal image from ~2 meters

Sample thermal image from ~3 meters

Curious mockingbird investigating our thermal cameras

Thermal image capturing in action

Thermal image capturing in action

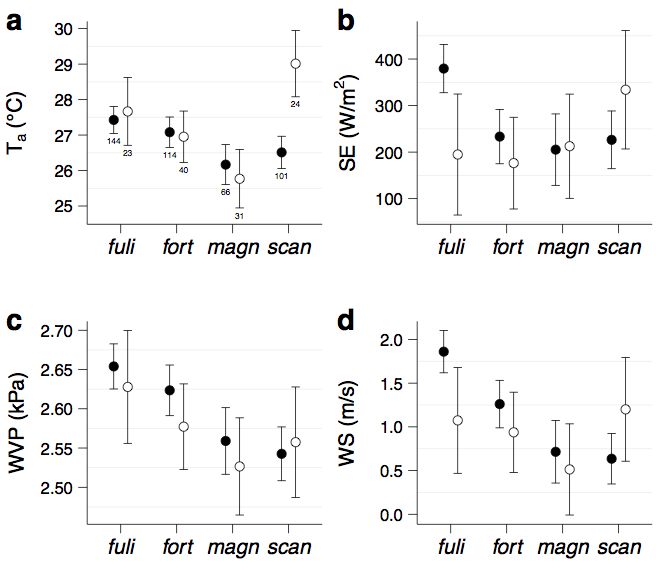

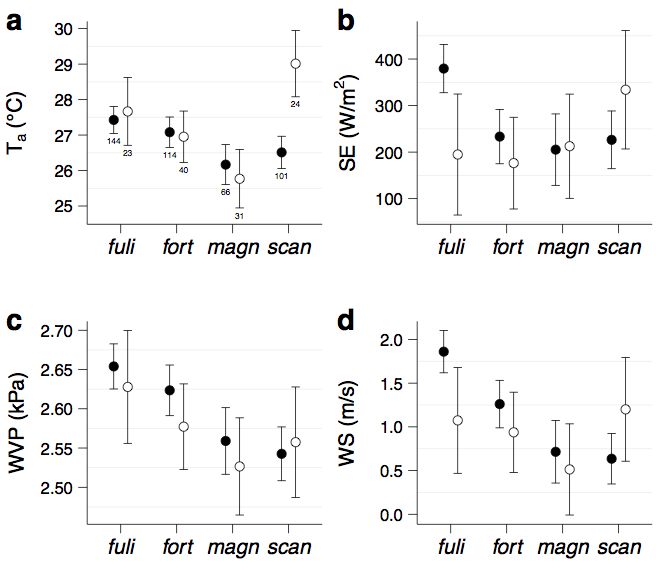

Summary of the observed microhabitat differences from our field thermography:

Mean (± 95% CI) values of key environmental variables (ambient temperature, solar radiation, water vapour pressure, and wind speed) obtained during one month of thermal image acquisition in the field grouped according to species of Darwin’s finch. Sample size for each species are the numbers depicted beneath the points. (Names below are abbreviations of the species: Geospiza fuliginosa, Geospiza fortis, Geospiza magnirostris, and Geospiza scandens). This figure is derived from data in our study, but was not included in the final version for reasons of conciseness.

Field based thermography

In addition to the discoveries listed above, we think that this study will prove useful for others considering a non-invasive, but quantitative approach to assessing thermoregulatory responses in the field. Infrared thermography is a camera based approach to capturing surface temperatures of objects. Bird surface temperatures are a function of the bird’s own internal heat production as well as their balance with solar heat gain and environmental heat exchange. We have tried to provide a detailed materials and methods in this paper’s supplementary in order to assist others who might be considering this approach in their field work.

How did it all happen?

We really need to thank and acknowledge Dr. Russell Greenberg for initiating and facilitating many of the ideas presented in this study, and who sadly passed away before the manuscript was written. In 2009, following my publication in Science, and a follow-up review paper in American Naturalist, I received an email from Russ, asking for my opinion a study about bill size dimorphism he had recently published on. In his study, he observed bill size differences amongst subspecies of sparrows and had just read my paper and wondered if some of his observations could be based on thermoregulatory constraints and the role of the bill in heat exchange. This discussion eventually led to one of my students, Viviana Cadena, going to work with Russ Greenberg and Ray Danner at the Smithsonian Institute and led to publication in 2012 in PLoS.

During this time, Russ and I opined about going to Galápagos to test our hypotheses in Darwin’s Finches. We put together a proposal and submitted it to the National Geographic Society, and received news of the positive outcome of the funding in October 2012. This good news was met with sad news, however, as Russ had recently been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. We did, however, get to work together in the field. In April/May of 2013, Russ, Ray, and myself travelled to Galápagos, where we met up with Jaime Chaves, and conducted the study now published in Functional Ecology. We might have been slower at writing up our work than you were, Russ, but we finally did it!

Citation

Tattersall, G. J., Chaves, J. A. and Danner, R. M. (2017/2018), Thermoregulatory windows in Darwin’s Finches. Funct Ecol. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12990

Funding

Research funding for this study was kindly provided by the National Geographic Society, the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, the Galápagos Institute for the Arts and Sciences-Universidad San Francisco de Quito Grant, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2014-05814). Logistical support was kindly provided by the Charles Darwin Research Station and the Galápagos National Park. Permits to conduct research were provided by the Galápagos National Park Service (Authorization No. PC-05-13).

Data Accessibility

Data will be made available on Data Dryad: Dryad entry doi:10.5061/dryad.t4k41.