Despite being a major event in early tetrapod evolution, many living fish species occasionally leave water, but the reasons are not always obvious. Some do it to feed, some to escape predation, and some to cope with poor water quality, although rarely for long periods of time. Another intriguing possibility is that fish may use land to help regulate their body temperature.

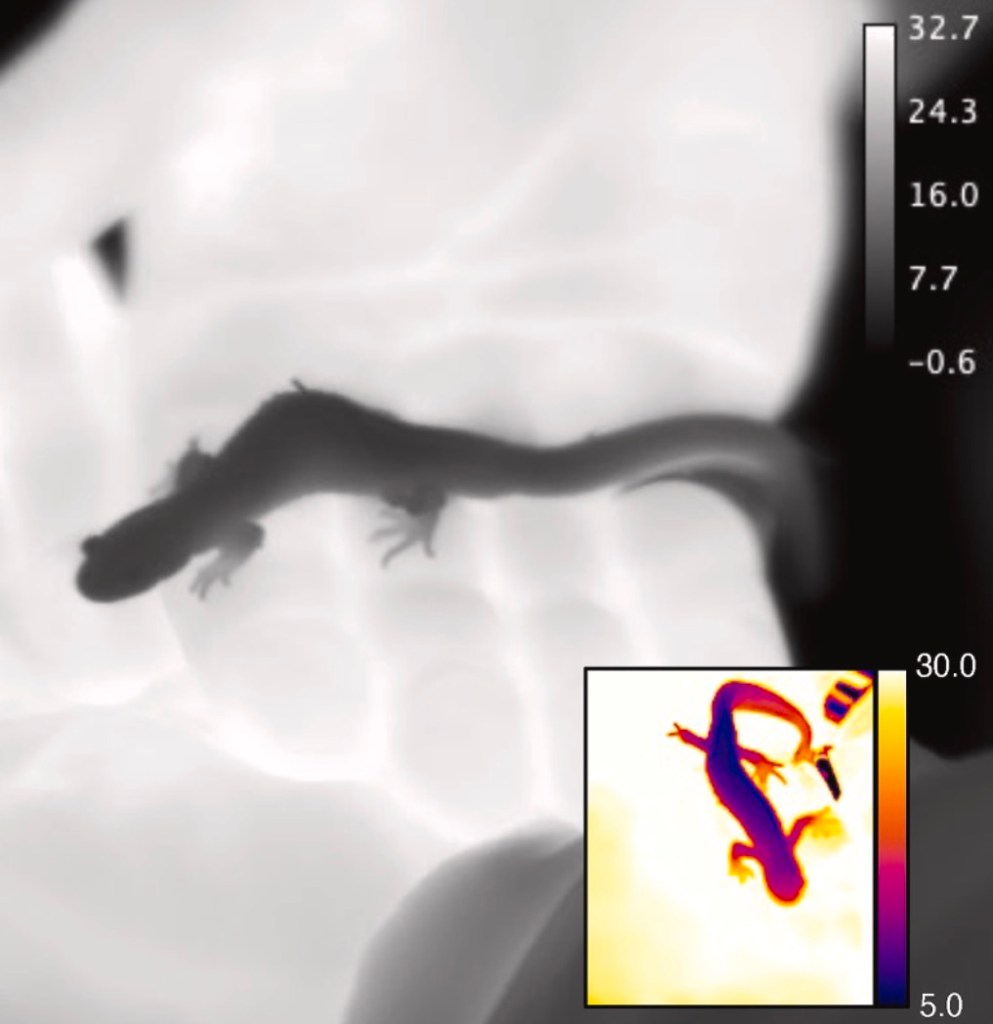

The mangrove rivulus (Kryptolebias marmoratus) is a particularly good species to explore this question. This small tropical fish is famous for its ability to survive on land for weeks at a time, provided the humidity levels are high. When water gets warm, mangrove rivulus will often emerge onto land, where evaporative cooling can rapidly lower body temperature, as we showed previously (https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2015.0689). But leaving the water also comes at a cost: gas exchange becomes much more difficult, leading to temporary oxygen limitation and CO₂ buildup.

In many ectotherms, low oxygen levels are known to shift thermal preferences toward cooler temperatures. That led us to ask a simple question: when rivulus go onto land, do they actively seek cooler temperatures than they would in water?

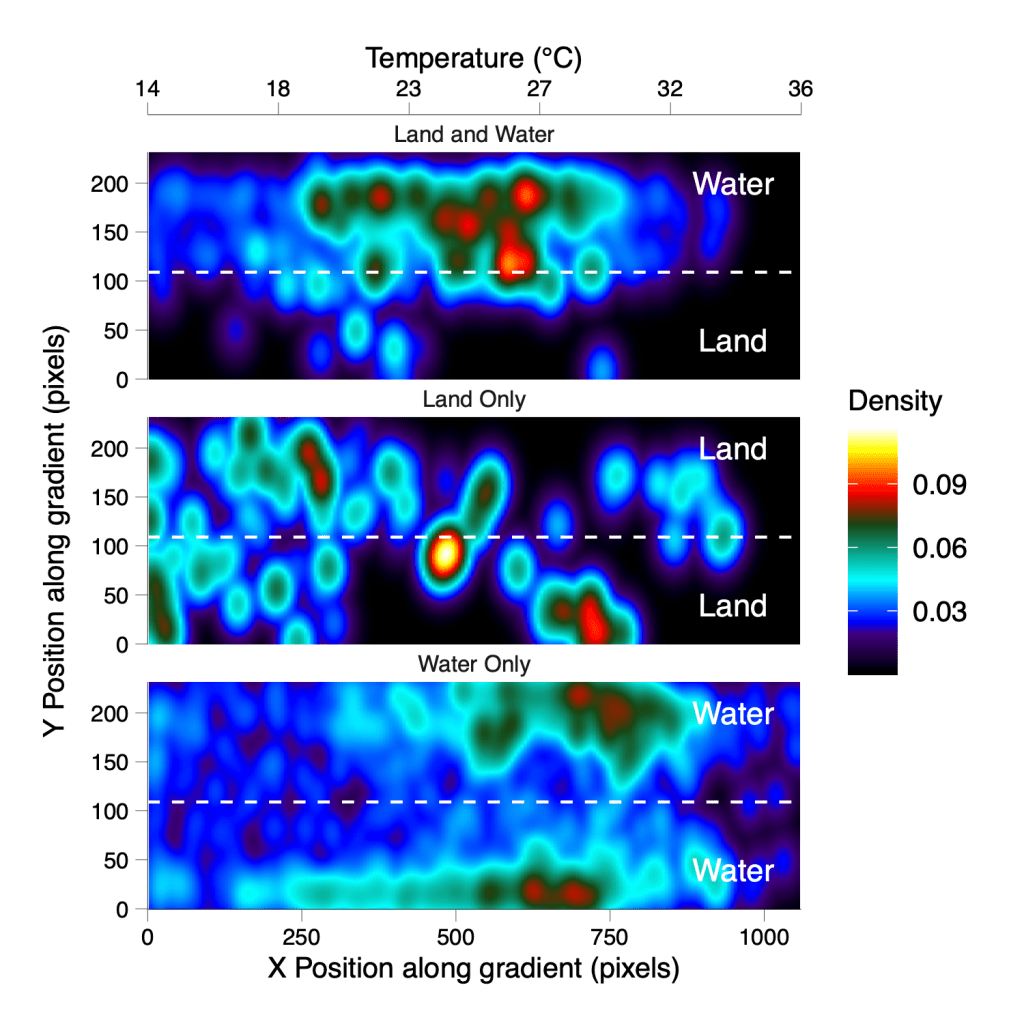

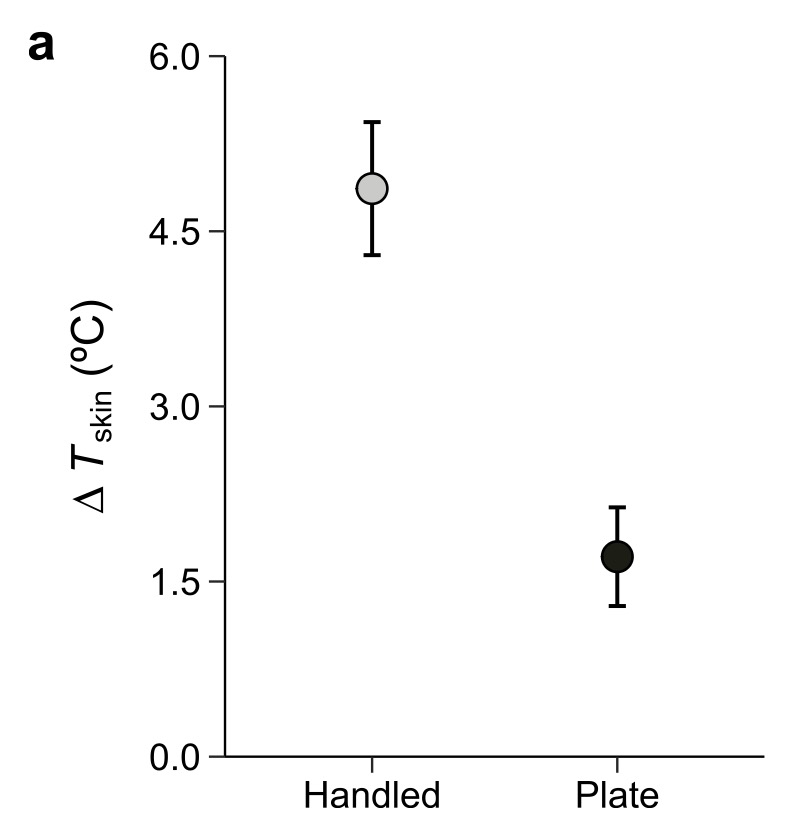

To test this, we (former Honours students Katlyn Dundas and Philip Bartel) gave fish access to choice of temperatures along a thermal gradient under three conditions: water only, land only, or a combination of both. What we found was striking. Rivulus only selected cooler temperatures when they were on land. When confined to water, their preferred temperatures remained higher, even when the same thermal options were available.

This suggests that their terrestrial emergence is not simply a passive escape from warm water to benefit from evaporative cooling. Instead, fish on land appear to actively choose cooler environments, which is a response consistent with anapyrexia, the deliberate reduction in the regulation of body temperatures (analogous but quite different from fever). In this case, leaving the water may help offset the physiological challenges of breathing air through gills that are adapted for water.

Together, these results add a new piece to the puzzle of why some fishes venture onto land. For mangrove rivulus, emerging from water may provide more than just temporary cooling. It may fundamentally change how they regulate temperature when oxygen becomes limiting.

The study is now available at the Journal of Experimental Biology website, citation below.

Citation

Dundas, KE, Bartel, PB, Turko, AJ, and Tattersall, GJ. 2026. Terrestrial emergence reflects lower thermal preferences in the mangrove rivulus (Kryptolebias marmoratus). Journal of Experimental Biology, 229 (4): jeb251829. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.251829

Many thanks to Brock University Library open access fund for supporting publication in the Journal of Experimental Biology!