Measuring body temperature should seem straightforward, but in ectotherms, the act of measuring can be part of the problem. For especially small amphibians in particular, common approaches like cloacal thermometry require restraint and direct contact, raising the possibility that handling itself alters body temperature before it is even recorded. In this study, we asked a simple but important question: does brief, gentle handling measurably change the body temperature of salamanders?

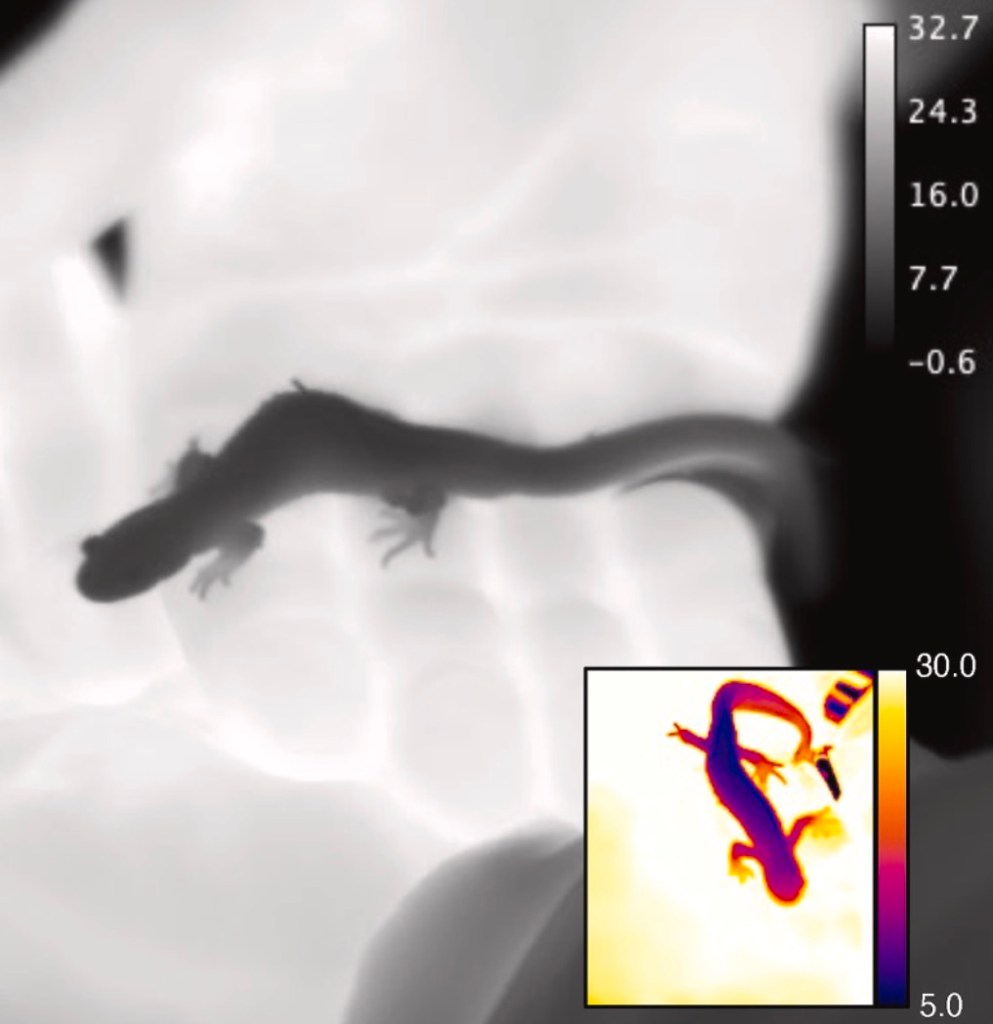

Using infrared thermography, we examined how short periods of handling affected skin temperature in two closely related mole salamanders, the blue-spotted salamander (Ambystoma laterale) and the spotted salamander (A. maculatum). We also combined field measurements with controlled laboratory experiments to tease apart the effects of physical contact, heat transfer, and behaviour.

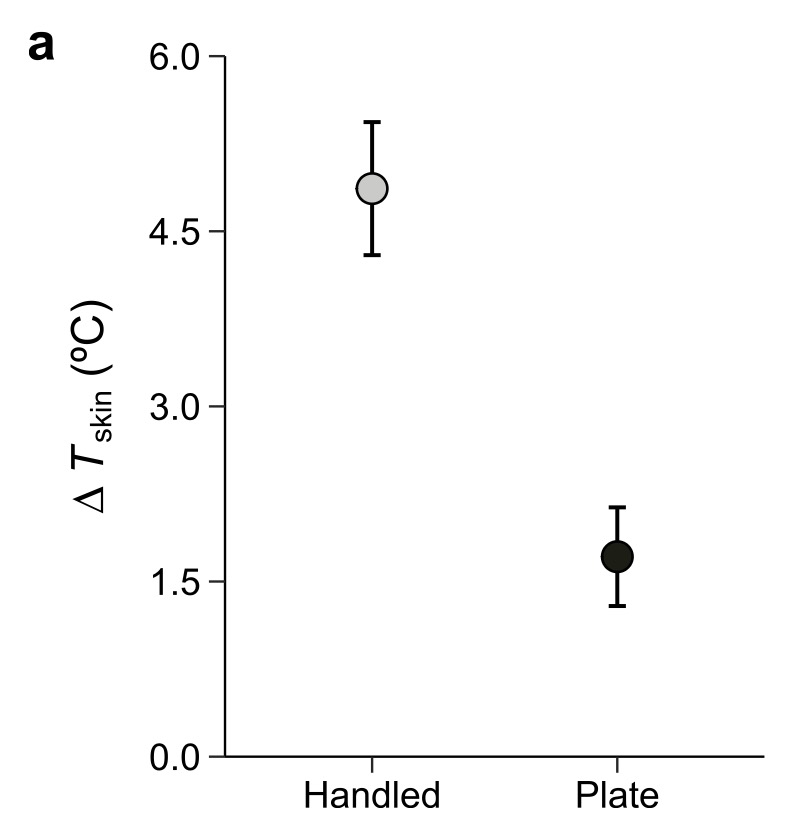

The answer was clear. Even short handling periods caused salamanders to warm rapidly. In the field, handled animals were consistently warmer than unhandled controls, with the head warming more than the rest of the body. Not surprisingly, smaller salamanders showed larger temperature changes, suggesting body size plays an important role in how quickly heat is gained.

In the lab, salamanders placed on a warm surface (set to hand temperature) also warmed up, but not as much as animals that were actually handled. This tells us that handling is not simply about contact with something warm. While we don’t know precisely why yet, the most likely explanation is that salamanders manifest a stronger cardiovascular response to human handling and the heat that they pick up is transferred more quickly throughout the body.

Temperature changes matter from a behavioural perspective. Warmer salamanders were more likely to become active, regardless of whether that warmth came from handling or from contact with a warm surface. That means handling can influence not only the temperature we measure, but also the behaviour we observe.

Taken together, these results highlight a subtle but important issue: brief handling can rapidly alter body temperature, sometimes at rates comparable to experimental heat stress studies. For researchers, this has implications for data accuracy in thermal biology. More broadly, it is a reminder that even well-intentioned, gentle handling can have unintended physiological effects, especially for small ectotherms.

Some caveats: this study is not to be interpreted as alarmist. Warming up from being in contact with warm temperatures is a pretty obvious expectation. These results would only have possible impacts for studies concerned with accurate temperature measurements or those that perform very brief behavioural observations during or immediately after handling (which is probably very rare) that are temperature dependent. And as one of the reviewers of the manuscript rightly pointed out, we measured surface temperatures, which will differ and lag with core temperature measurements.

We do note that there is a related study appearing in the same issue of the Journal of Thermal Biology highlighting similar cautions as this one, and that particular study actually measures core temperature of really tiny frogs!

Citation

Giacometti, D, Montes, LF, Denommé, M, Andrade, DV, and Tattersall, GJ. Handle with care: the thermal consequences of short-term handling in mole salamanders. Journal of Thermal Biology, 136: 104390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2026.104390