The following is a guest blog by Danilo Giacometti, MSc.

Background

By living underground or in burrows, fossorial animals benefit from protection against predators and climatic buffering. This seclusion, however, may lead to increased exposure to low O2 (hypoxia) and high CO2 (hypercarbia) levels in burrows. Hypoxia and hypercarbia are well known to impact respiration and energetics in both endotherms and ectotherms. If exposure to hypoxic and hypercarbic conditions persist over the long term (i.e., across generations), natural selection should favour organisms with a blunted sensitivity to gas exchange limitations. As such, fossoriality has long been associated with energy conservation. Most of the evidence in favour of fossorial species having low energetic requirements comes from work in mammals. By studying the metabolism of rodents, McNab (1966) suggested that fossorial species had convergently evolved low metabolic rates compared to non-fossorial ones. McNab’s logic was straightforward: given an energetic stressor (i.e., hypoxia and hypercarbia), natural selection favoured a physiological adaptation (i.e., low metabolic rates) that would minimise O2 depletion and CO2 buildup.

Almost 20 years later, this hypothesis was extended to explain metabolic adaptations in squamate reptiles by Andrews & Pough (1985). Although other researchers attempted to elucidate whether fossoriality had impacted the metabolism of vertebrate ectotherms (e.g., Kamel & Gatten, 1983; Ultsh & Anderson, 1988; Withers, 1981), most studies were limited by a small number of species used in comparisons, lack of phylogenetic control, and improper consideration of body mass effects over metabolism. Perhaps the most important consideration in this context comes from Wang & Abe (1994), who called attention to the fact that the metabolism of vertebrate ectotherms is intrinsically lower than that of endotherms. Thus, a further reduction in metabolism driven solely by fossoriality would be evolutionarily unlikely given the limited energetic benefit. In this sense, the impact of fossoriality on the metabolic rates of vertebrate ectotherms has remained unclear.

What did we do?

With this in mind, we addressed whether fossorial amphibians were selected for lowered metabolic rates compared to non-fossorial and aquatic ones in a phylogenetic framework. Building from a compilation of amphibian metabolic rates found in Chapter 12 of Feder & Burggren (1992), we collated a dataset with information on metabolic rates, test temperature, body mass, latitude, lifestyle, and phylogenetic relatedness of 185 species of amphibians (Fig. 1). Details on our methodology, inclusion criteria, and analyses can be found in our manuscript.

What did we find?

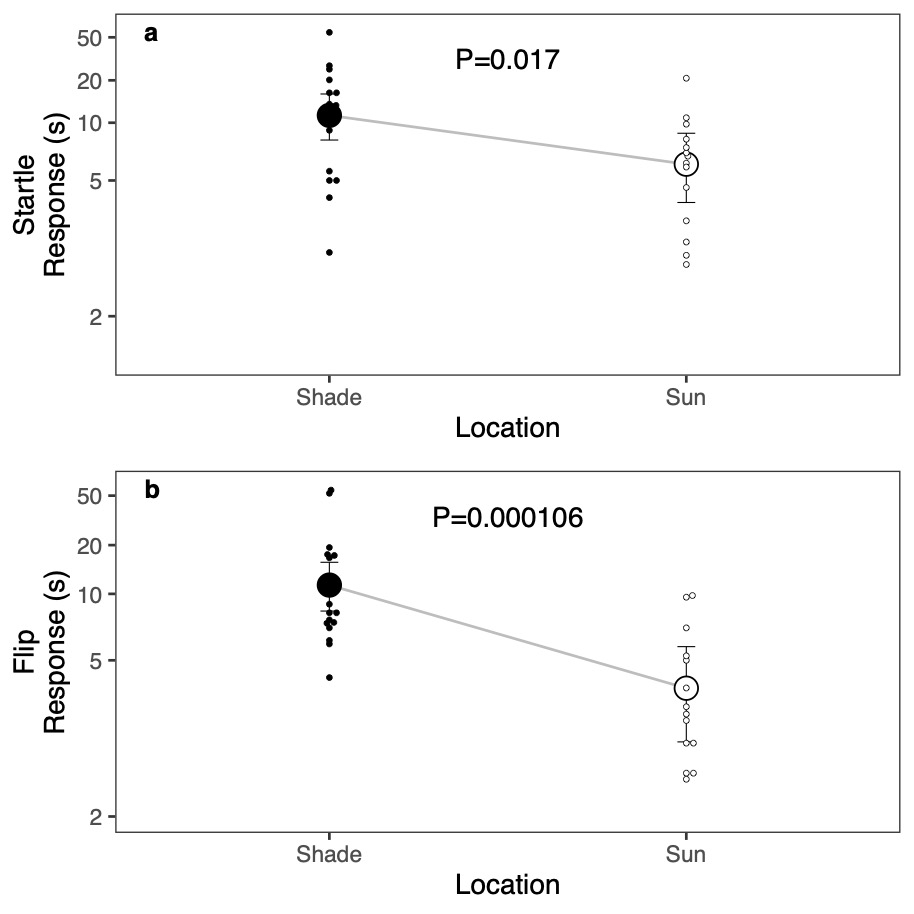

Thermal and body mass effects over metabolic rates

As expected, both test temperature and body mass explained differences in metabolism among species (Fig. 2). Metabolic rates increased with temperature; however, the thermal dependence of metabolism did not differ among lifestyles (Fig. 2A). Additionally, our results are in concert with the principle of metabolic scaling, as body mass was the primary determinant of metabolic rate variation after accounting for phylogenetic effects. In general, the larger the species, the higher its metabolic rate—once again, regardless of lifestyle (Fig. 2B). This finding fits in with the framework proposed by White et al. (2022), who argued that metabolic scaling is the outcome of optimised growth and reproduction. Considering that we found metabolism and body size to be inextricably correlated in amphibians, life history optimisation could be the mechanism behind our recovered pattern.

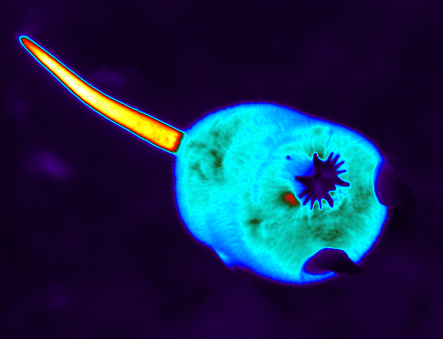

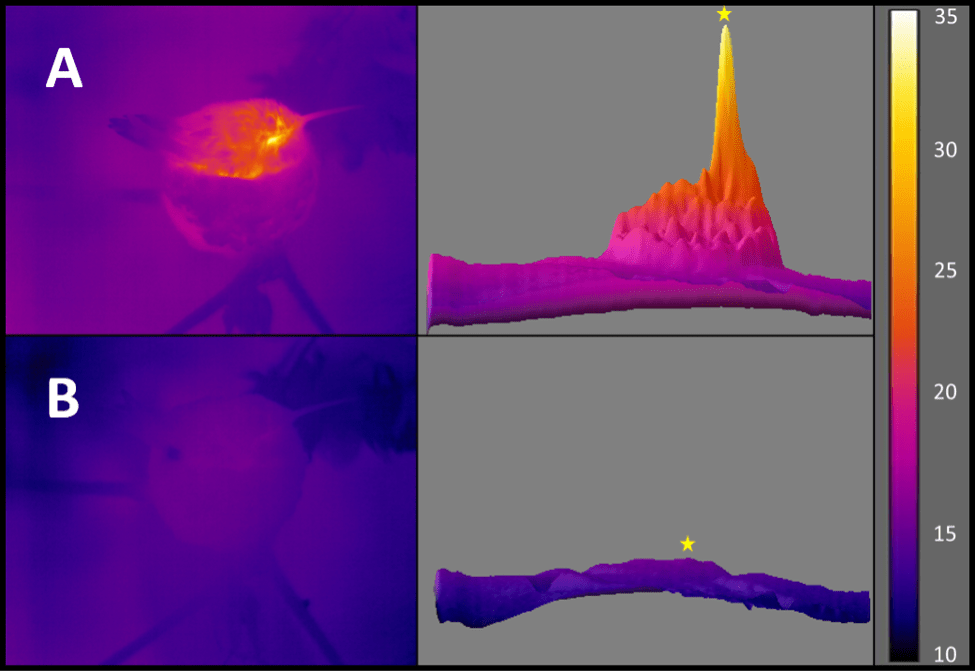

Unraveling the mysteries of fossoriality: potential roles of cutaneous breathing

Our results revealed that fossorial amphibians do not have lower metabolic rates compared to their non-fossorial and aquatic counterparts after controlling for body mass, temperature, and phylogenetic effects. We suggest that the low energetic requirements of amphibians, coupled with their efficient cutaneous and pulmonary respiration capabilities, may explain why fossoriality did not impinge on their metabolism. Preliminary work in caecilians showed that fossorial species can sustain energetic requirements solely through cutaneous breathing, suggesting increased reliance on skin breathing and enhanced control of bimodal breathing in this group (Smits & Flanagin, 1994). We suggest that further research into the blood respiratory properties and bimodal breathing capacities of fossorial versus non-fossorial amphibians should provide valuable insights into their energy-saving strategies.

Conclusion

Through a comprehensive comparative analysis, we bring to light the complex interplay of factors influencing the metabolism of amphibians. Our work emphasises the central role of body mass and temperature in determining metabolic rates and suggest the possibility that the unique respiratory physiology of amphibians may have contributed to offset the effects of fossoriality over energetics in this group. As research continues to unearth the mysteries of fossoriality, it promises to deepen our appreciation for the remarkable adaptations of these unique creatures living beneath the surface.

Our article will be freely available for eight weeks on initial publication. Read the full study here.

Citation

Giacometti, D and Tattersall, GJ. 2023. Putting the energetic‐savings hypothesis underground: fossoriality does not affect metabolic rates in amphibians. Evolutionary Ecology, In Press.

Acknowledgements

We thank Leonardo Servino for helping us obtain geographic coordinates for the species in our dataset. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped improve our manuscript. Research funding was provided by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant to GJT (RGPIN-2020-05089).