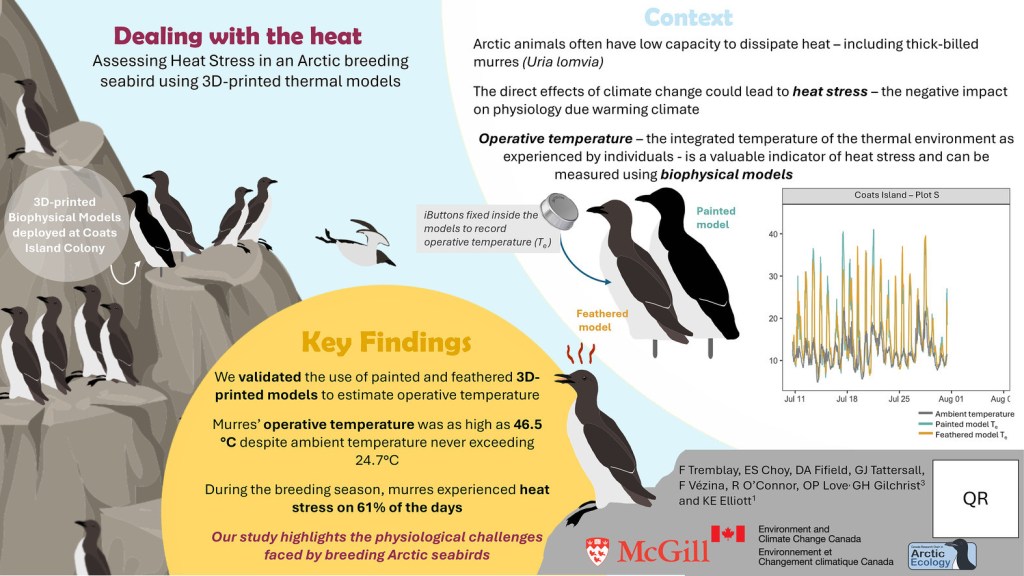

As the Arctic warms at an alarming pace, we’re learning that even cold-adapted species like the thick-billed murre aren’t immune to rising temperatures. This latest study, led by Fred Tremblay from Dr. Kyle Elliot’s lab at McGill adds to the growing understanding that cliff-nesting seabirds are experiencing heat stress far despite ambient air temperatures rarely exceeding 25°C. Using custom 3D-printed murre models painted to mimic the birds’ plumage, we measured “operative temperatures” (the actual heat experienced by an animal) on Coats Island, Nunavut. These operative temperatures soared as high as 46.5°C due to solar radiation and other environmental factors. In fact, murres faced heat stress conditions on 61% of summer breeding days, which can lead to significant water loss and physiological strain.

This work highlights the impact of climate change on Arctic wildlife and illustrates the value of biophysical modelling and how important it is to consider more than air temperature measurements in macroecology/macrophysiology (see https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12818 and https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5721).

These models, in combination with infrared thermal imaging, offer a non-invasive and cost-effective way to measure real-world thermal conditions, paving the way for better predictions of species vulnerability. With males incubating eggs during the hottest parts of the day, this heat stress isn’t just theoretical. It could shift breeding success, survival rates, and long-term population dynamics. These type of studies demonstrate the importance of microclimates in assessing the threats facing Arctic fauna and animals around the world.

For access to the study please follow the link in the citation below.

Citation

Tremblay F, Choy ES, Fifield DA, Tattersall GJ, Vézina F, O’Connor R, Love OP, Gilchrist GH, Elliott KH. 2025. Dealing with the heat: Assessing heat stress in an Arctic seabird using 3D-printed thermal models. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 306: 111880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2025.111880